Meet Rob. Robert. Roberto. Beto. Robi.

Robert grew up in the small, unincorporated, rural community of London, California, where he experienced firsthand the challenges faced by underserved populations, particularly the lack of local leadership and resources. After spending years in the Bay Area and Los Angeles as a student and teacher, Robert returned to the Central Valley, motivated by the stark contrast in resources between affluent areas and his hometown.

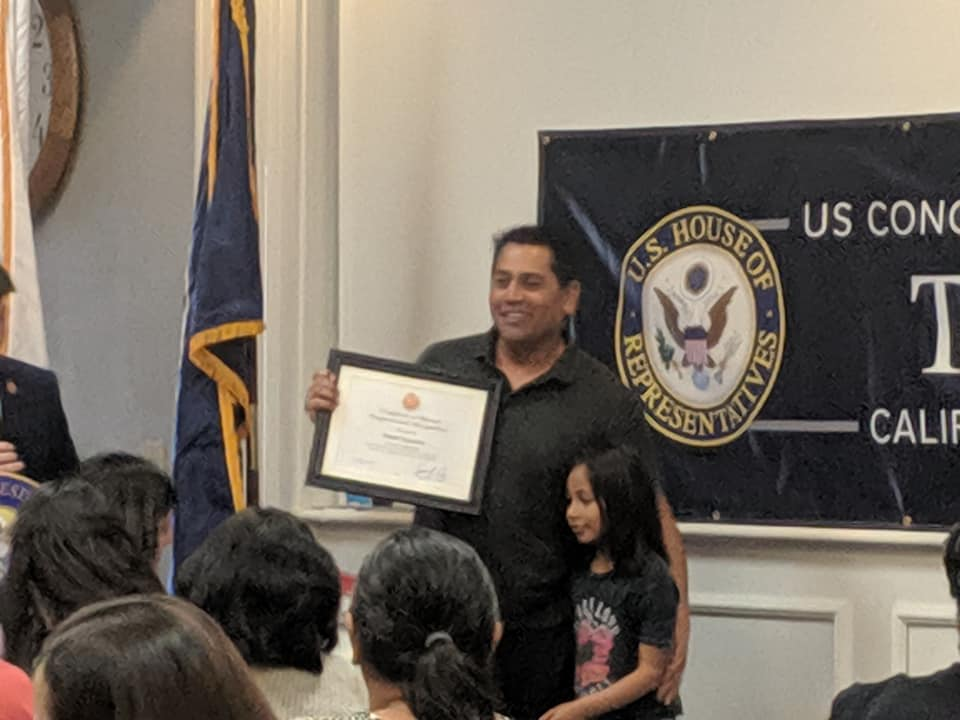

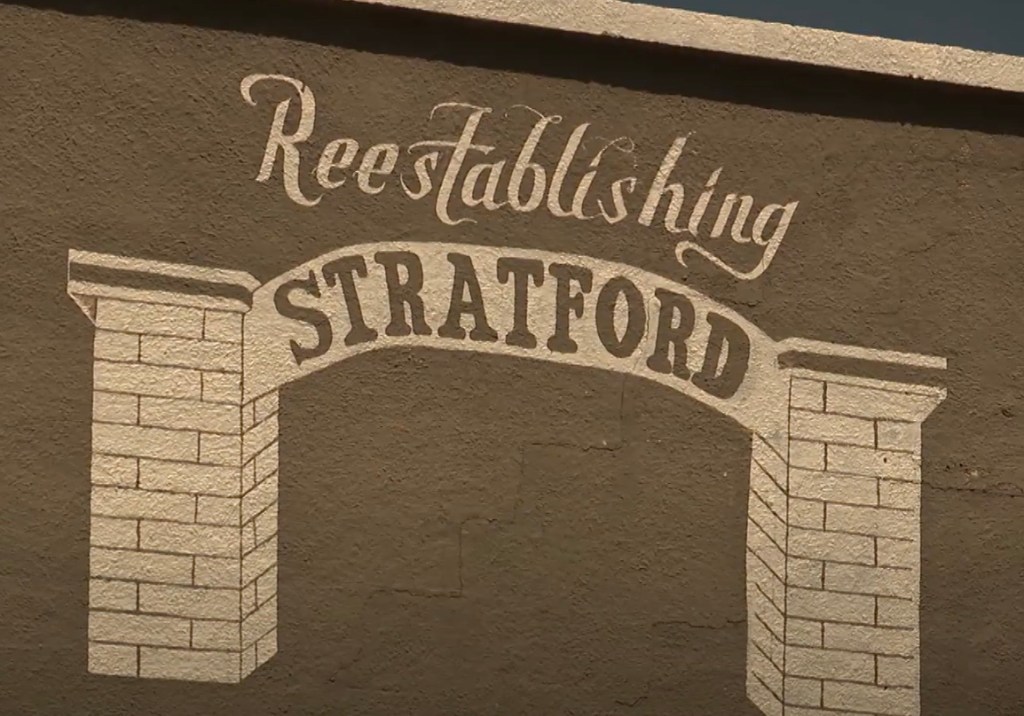

Inspired by the lack of basic amenities such as libraries and fresh food in London, Robert (along with his co-founder of Reestablishing Stratford), spearheaded the creation of a library in his hometown, learning nonprofit skills along the way. After moving to Kings County, he partnered with Ramon Chavez, a local resident and former gang member, to form a nonprofit aimed at revitalizing Stratford, another underserved, unincorporated community. Over the past decade, their efforts have included food distributions during COVID-19 and ongoing advocacy for community improvements, such as securing a safe turning lane into Stratford. The conversation highlights the importance of grassroots leadership, community partnerships, and persistent advocacy in addressing the needs of rural, underserved areas in California’s Central Valley.

Robert’s Story: In His Own Words

Q: Hi Robert, how are you?

A: Good, good. I’m on summer vacation right now, so that means it’s always good.

Q: Awesome. Are you a teacher, professor? What do you do?

A: I like to joke that I have 17 jobs, but one of them is the lead teacher for the education academy at Sierra Pacific High School.

Q: We’re hoping to do a profile to amplify the voices of people that are working in the Central Valley area. Why don’t you just tell us a little bit about the work that you do?

A: Okay, so one of the things that I like to do that helps people kind of understand where my work came from or how it derived was kind of start with the origin story: I was born and raised in a small unincorporated rural community called London, California. London’s in the Central Valley in Tulare County, and it’s in between the cities of Kingsburg and Dinuba. It was named London because when the guy who purchased the property in the 1950s, there’s a lot of thick fog in the Central Valley.

And he said, this is thick as London fog.

So he called it New London.

The new part dropped off after I returned to the Central Valley.

But anyway, I started there.

And growing up in that area, you become very cognizant of the underserved population because you’re a part of it.

You’re experiencing it.

And one of the things that happens in the Central Valley, and probably, you know, you guys are familiar with this from other areas of California,

is that when you’re in an unincorporated community, you don’t have a leadership board of residents that live within the community.

For example, I live in Lemoore right now.

We have a mayorship.

We have, you know, all these leaders who make decisions about a town they live in.

In London, because it’s an unincorporated community, you know, a group of houses, if you will, primarily made up of farm workers, we don’t have a group within the community that really advocates for us.

And so all decisions for us are made by the county.

Obviously, none of the county leadership lives in London, so they’re just kind of assuming what the needs are. I’ll fast forward to 10 years in the Bay Area for college, another 10 years in Los Angeles, Santa Clarita as a teacher.

And now I have a wife and a family.

And I’m becoming even more conscious of how students specifically are underserved in certain areas.

Santa Clarita, are all of you familiar with the community of Santa Clarita?

Q: We are. Quite different from Stratford or London, no?

A: There’s a lot of leadership. There’s a lot of resources.

And so in my last year there, living in that area, I had two young boys, four or five years old and a very young daughter.

And we went to the grand opening of the multi-million dollar library.

It was created in Santa Clarita.

Santa Clarita is a combination of five different cities, including the most visible by Valencia, which has Magic Mountain.

I see all these resources, and my kids are taking an escalator from the bottom floor up to the top [of the new library]. There’s fireplaces, there’s tech areas. And I’m like, oh, my God, look at how many resources we have here in Santa Clarita.

And it just hit me like a ton of bricks.

What about the kids of London?

What do they have?

I go back home and they have no library.

They have no schools.

They have two convenience stores that don’t serve fresh produce.

All the things that you guys recognize are important are missing.

And so at that point, that’s my origin story is I decide that I’m going to try to bring a library to my hometown.

Q: What did you do?

A: The library took about three to five years and I had no experience in nonprofit work.

It was a trial by error thing.

And luckily, by the grace of God, because, you know, there’s a lot of prayer involved in this, it became a reality.

And I learned, you know, some basics.

I was mentored by a few people who work in nonprofit for a living.

So I learned some basics from them.

And I also started to understand the power of social media.

And I started to heavily utilize Facebook as my main source of promoting what was happening.

Long story short, the library becomes a reality.

And now I’ve got the bug, right?

The bug that says, hey, there’s some power in this and you can make a huge difference now that you know, you know, somewhat of the journey and the steps necessary.

And so then we relocate to Kings County.

And in Kings County, it was a mirror of London.

It was called Stratford.

And Stratford is a small, rural, unincorporated community primarily comprised of farm-working families, just like London.

So I just feel like I’m back home, right?

So a 20-year circle out in the world and then back home.

And my mom lives there. I live with her for about a year and a half. During that time she says, ‘hey you did some great work for your hometown, but I live here and right now you live here. Why don’t you do some of that work here in Stratford?” So, immediately I start looking for a partner and I find Ramon. I saw he was a guy building a basketball court from scratch in the open area of an abandoned, dilapidated building. So the building walls had crumbled. This guy had swept it out, set up a basketball court, and kids started hanging out there. I’m like, I need to know who did that. I start looking for a group of people, but turns out it’s just one guy. His name is Ramon Chavez and he’s a lifelong resident of Stratford. I partnered with Ramon.

I said, “Ramon we can do bigger things together.”

He’s like, “Well, what do you mean?

I go, “let’s make our own 501c3. Let’s make a non-profit here. What do you want to call it?

“I want to re-establish this community because at one point we had three grocery stores. We had five gas stations. We had a thriving restaurant. The downtown area was bustling with activity and commerce.”

It’s a ghost town right now. 90% of the Main Street businesses have shut down. Ramon wants to re-establish what it once was. And I also wanted to do the same. That was 10 years ago. Now through 10 years of work, again, a lot of trial and error, a lot of mistakes, a lot of learning on the fly, we’ve been able to gain some momentum in our community and we fought for a few things.

One of the most important things we’ve done over the last couple years was during COVID. We were able to provide regular food distributions in partnership with some local organizations. That’s where we met Valley Voices. Valley Voices is the organization that covers most of Kings County

Q: What are some of the obstacles or projects Reestablishing Stratford is trying to take on?

A: Reestablishing Stratford is trying to get a safe turning lane into the community of Stratford. People who visit our community always say, you guys don’t have a turning lane to get into your community? One of the busiest highways in California is the 41. 41 will take you from any Central Valley community through up into Pismo, the Central Coast, which is a highly sought after destination.

Q: At one point you talked about how Stratford used to be like a bustling little town and now it’s a ghost town. Can you share about why that happened?

A: This happened 30, 40 years ago. I wasn’t around for it, but I’ve asked and what I gathered from these conversations is that part of it was the water issue. And a lot of our resources and a lot of our commerce was generated by our farmers in the local area. At one time, when Stratford was thriving, there were many large farming companies in the surrounding area. When the water starts to go, right, farmers will try to find places where they have easier access to water or they get out of the business altogether. When they pack up, there go the jobs. There go some of the local businesses. There was this large mass exodus of at least half the population. This was in the 90s, early 2000s, maybe a little earlier, that the vitality started to fade. From my conversations, the heyday [of Stratford] was from the 1950s to the 1970s or 80s. Businesses slowly started to close shop. Farm companies started to relocate to other areas. And so I think that’s where that started. Once resources are taken, that affects the residents who are still there. One thing that I’ve learned more as I’ve gotten older is how impactful the subliminal or subconscious messages are that are being delivered. One of my theories is that if you live in a community like Stratford and you see it thriving and then slowly over time you see people leaving and you see businesses closing down, right, and physically it’s changing, right? It’s getting dusty and shut down and closed. There’s a message being sent to the brain that where I live is no longer valued. It is not a place to stay and thrive but rather a place to escape from. You want to get away from there. And that’s not just a Stratford issue. I think to some extent that is kind of a central valley issue. When you talk about the central valley, I mean, even in a lot of movies and stuff, people jokingly reference Fresno as a place you don’t want to be. You know, like, “oh, I’m stuck in Fresno,” or, “Dude, if you don’t step up, you’re going to end up working for our Fresno office,” right? Like, it’s not an ideal place. In media, it’s kind of been sold as the worst place to be. One of the most impactful podcasts out there is Joe Rogan. I kind of look up to him and what he’s been able to build. But one of the things he said one time that really bothered me ihappened when he was trying to reference this soulful restaurant that he had gone to. It’s very novel because they serve Kool-Aid at this restaurant. They have amazing fried chicken and waffles. So he’s trying to recall the town. And as he’s trying to recall the town, right, this is not verbatim, but kind of what he said, and excuse the language because I’m just trying to illustrate a point, but he’s like, “I had the best fried chicken. What’s that shithole out there in the central? Man, just like crackheads. Fresno. Yeah, Fresno.” Right? He was trying to reference a restaurant. He had a myriad of insults about our area as he did that. Remember, he’s the biggest podcast in, I think, the world right now. It’s not just the United States. And so that message is heard or sent a lot. I think that that plays a role in our apathy. Okay, well, I’m from a place that’s undesirable. It physically doesn’t look like a place where people would want to come to. What can I do to change this?

Q: Rob, what else is going on with environmental justice issues around Stratford? Anything in particular?

A:The other one, and probably the most impactful, was in 2018, our water well broke. The water levels were low and sucking up sand into the well and it clogged it. We didn’t have a backup water well at that time. The drought is part of it, but the drought doesn’t dictate us having a backup well. Every town, any town in America, has multiple water wells. This one doesn’t work. We didn’t have a backup. The backup was broken. It was like, well, that, you know, we understand the drought and the water situation is a struggle, but that does not, that doesn’t justify not having a backup plan. So the backup plan wasn’t there. We became the backup plan. I felt honored and terrified that the first phone call made from the community of Stratford wasn’t to the county or the city. They called us [Reestablishing Stratford]. Immediately, I called our local casino, which is Tachi. Tachi is only about seven, eight miles away. I said, can you help us? They immediately, within an hour, sent three large pallets of water. And then we started getting on social media and going door to door telling people to come to the water district and pick up water. We kept the water going through various donations and contacts for that week and a half.

Q: You mentioned a turning lane earlier. What is that really about?

A: This is a Caltrans issue right now. We had a town hall meeting that was in response to 10 years of near fatal accidents because we have no turning lane. We finally were able to get Caltrans to hold a town hall meeting. The next one will be August 28th. There’s multiple reasons why there should be a turning lane into a community, right?

Q: So one question is if you were to give advice to somebody, a young person wanting to make a difference, how should they start? What should they do?

A: If I’m a young person trying to make a difference in a community, I think the first thing I would identify is a mentor who’s already doing the work that I’m seeking to do. In my case, I was an adult when it happened to me, but my saving grace, the thing that kept my hope alive and guided me was these mentors early on who, for example, a guy who ended up being the county supervisor of Tulare County, Eddie Valero, took an interest in my work early on. He started to mentor me and kind of help me navigate the county system and the political side of things. Matt Naylor, who was a local pastor, and he had been running a nonprofit in the same community of London where I grew up in, he took me under his wing and started to teach me the difference between just blindly giving things away, what he called toxic charity, and being more intentional and strategic about what you’re providing to people. So number one, I would say identify a mentor in your area who’s doing the type of work that you would like to do. Number two, identify local partners who can support you in that work. And partners, I mean my local nonprofit organizations. Even if they’re not trying to serve the same need or population, they’re still having to navigate some of the same loopholes, like what is a 501c3? How do you apply for that? There were a lot of things early on that I was saved from because I had mentors and I had partners who believed in what we were doing. That would be step one for a young person. Step two, I would recommend that they get involved in their local school government. I feel like ASB serves students so well in just a simple idea. Here it is. If I’m a regular high school student, I walk into the school dance and I buy a ticket and I enjoy myself. I don’t question who hired the DJ. I don’t question who showed up early and did all the decorating. I don’t know what the budget was for that event. I just simply show up and dance. But when I’m ASB, I know who the DJ was. I know how much it cost. I know the nuts and bolts of putting an event together, a successful one, the marketing of that event, the organizing of the group that puts it on. There’s all these leadership skills that you need when you’re trying to help your community that you learn through your school leadership. I would strongly recommend identifying a mentor and getting involved in your local ASB, whether it’s at the grade school level or high school level.

Q: So let’s go back to where we started. Do you go by Rob or Robert?

A: My name is a funny conversation because it’s evolved over time with just different people and what they’re comfortable with because I’m very accommodating. When I was in college, they changed it to Roberto.

I’ve never been called this. It’s not on my birth certificate.

So I was like, yeah, sure. And then when I say my name quickly as Rob Isquierdo, which is my last name, watch when I say it together, Rob Isquierdo. It sounds like I’m saying Robbie. Oh, hey, how you doing, Robbie?

Q: Okay, Rob, tell us more about Reestablishing Stratford.

A: There’s seven of us, and they’re getting these things done for our community. We’re no different than any other resident from Stratford, other than we’re willing to put ourselves out there. Put in the work. It takes a lot of work, yeah. Yeah, and I think that’s why we’re only seven. But here’s the other thing: we’ve all had a time in our life when we’re in survival mode. I’m just trying to make the bills. I have no extra energy to serve my community. I need to get compensated because my own kids are starving or unemployed, et cetera. And so in towns like this, you have a large population of people in survival mode. I’m trying not to get deported, and you want me to go out and volunteer and pass out food to others? I need that food for my own fridge. So we have to help the overall population so that they are at a point where they have a little breathing room to go out and help others. I’m blessed with employment. I’m blessed with a home. I can go to Stratford, serve, and then come back to this room here and all the resources I’ve been blessed with. So it’s easy for me. Well, not easy, but it’s a lot easier for me to think outside of myself. The people of Stratford don’t have that luxury right now, and I don’t blame them. I’d be the same way. So when we have distributions, we don’t hand out food until 10 a.m. The lines start at 7:30 a.m. because they are so fearful of us running out of food before they get their turn. This is what keeps them going through the month with a $12 dozen of eggs that we had in the past and the weight.

Q: So, how’s it going then?

A: We actually have a coalition that we just formed. It’s myself and our organization. It’s UC Santa Cruz. And it’s, again, another blessing from Sacramento. The Sacramento source, I can’t even reveal him because he’s in the mix to the point where it would jeopardize his job. But he’s like, I’m sick of Sacramento focusing on Sacramento and surrounding areas and then the big cities, LA, San Francisco. And he says, we don’t really spend a whole lot of time discussing or addressing the Central Valley. And he says, I’m sick of it. And so he drives to our events and shows up. And I’ve always, for the last year, like, why does he come? We have nothing to offer this person but a series of issues that need to be addressed. And he is an advocate for environmental justice. And so what they’re doing is we are having these monthly meetings and we’re identifying potential grants that we can write to include UC Santa Cruz. The professor from UC Santa Cruz, he’s fine. He’ll tell you, Javier Gonzalez, let me see if I can get his stuff here, Javier Gonzalez. And he’s the one who’s really pushing for this. And what he does is he’ll bring down these $10,000 drones and he’ll fly them in Stratford and he can identify the methane emissions from the local dairy. He can identify what types of particles are being put out there. That would be great to see in a documentary, the drones flying, that kind of thing. Yes, there’s his link right there. But he’s, yeah. Yeah, see, this might be Stratford right here on the website. No, because we don’t have the palm trees. Yeah, he comes about once a month. And so, Charlie, there’s this big movement to identify what the levels of pollution are in Stratford and to then try to create policy to reduce that by not allowing business to set up shop. Because what we’ve seen this pattern is places like Wonderful, they’re going to go and take the least path of resistance, right? They’re not trying to set up shop in LA or San Francisco because those places know how to advocate for themselves. Credit to them, good for them. But small communities like us who are not as quite organized, they want to exploit the hell out of us. Is there any effort to organize Stratford into a town or a city? I mean, is it too small? I don’t know anything about how people do that. That has been a conversation in the past, but the bigger conversation that we’ve been having is just to advocate so that the problems don’t get exasperated. For example, it’s like, all right, well, wonderful, successfully set up shop here. Well, let’s go take our admission-bearing company and also set up next to them. So they kind of follow suit. They watch and see, guess what? And so the environmental justice is us just trying to protect our small community, but also serve as a pilot program, if you will, to teach other towns like London and Ivanhoe and all these small unincorporated areas how they can advocate for themselves as well. But we’ve just been blessed with a strong coalition with Javier Gonzalez Rocha, with Rafa from Sacramento, with another environmental group. I don’t remember Ruben’s group, but Charlie, it’s about four or five organizations who are trying to help us with the environmental justice aspect. And the biggest thing they’re doing is they’re setting up air sensors throughout Stratford, right? And so we can view our air quality, and they’re called purple sensors, I think. I’m familiar with those. Yeah, purple sensors. So obviously, okay, and there was another thing, and we don’t have to leave the environmental justice thing, Charlie, but I do want to throw this in too. Something that I think the most impactful thing between the basketball court story, but then the other thing that really hit me was the fact you said there’s really nothing fun for the kids to do. So like, if you hold an event, that’s really all they get all year. So I’m thinking of these kids, they have bad air. Sometimes they don’t have water. They don’t have anywhere to go do anything fun. You know, I hear Ramon was in a gang, right? So and he’s a child of Stratford. So like, what are these kids up against? Like socially, environmentally, educationally? I would love you to talk about the kids a little bit and, you know, the health issues they’re dealing with or, you know, things like that. Well, the kids were the actual original inspiration for putting this together. Ramon has a very big heart for the youth and he’s always asking, you know, what about our kids? Because he went through it. And so one of the arguments he made early on was the school does an amazing job of providing resources and sports and activities from the times of 8 a.m. to 3 to 30 p.m. So that time for those kids, you know, is instructional. It’s thriving. It’s fun. But you have all this other time from 3.30 until the next morning or Saturday and Sundays where if as a young child, I don’t have anything, you know, to do, I sometimes as I get into my adolescent years, I make bad choices. You know, a lot of our bad choices are just sometimes a combination of curiosity and boredom. Right. And so that was the big part of it. And so we try to bring youth sports to Stratford so people don’t have to drive out of town. So Sheila Taylor’s done a great job of that. So she’ll bring seasonal stuff. We’ll have a football season. We’ll have a soccer season. You know, obviously want to bring more and more as we can. But it’s been this kind of careful balance and dance between not disrespecting our educational institution because they do a great job. Right. But also trying to find ways to fill the gap at that time, that free time, that downtime, especially for the student whose families are full time workers in survival mode who don’t have the resources to do the quote unquote vacations or leave town for entertainment purposes. Right. Things like that. So we’re really trying to focus on giving them not only options on things they can do, but also hopefully educating them on how they can grow up to be advocates for their community. Right. Because they are the future. Reestablishing Stratford, our average age is I think 30, 35 years old. We’re moving on. We need people to replace that. That’s so young compared to the organizations where 35 is like. Yeah, you can double that for me. Yeah, I’m 52. So I’m not referring to myself. I’m on the older end of it. But yeah, so for the youth, like that was the whole Ramon’s whole thing was the youth. That’s why he tried to build that basketball court. That wasn’t for the adults. It was for the kids. And so we are constantly trying to find ways to keep them busy with positive activity. And that can be very challenging. How many people live in Stratford? That that’s a very tricky question because that fluctuates. Right. So let’s say, for example, we are not in the current political climate. Yeah. And we have a lot of workers in the area. We can be, you know, up to fifteen hundred. But if ice is on the prowl and people are not feeling safe about going out to the fields and working here so they can’t make money. Right. They have to move on. We could be as low as seven to eight hundred. So the census is never accurate in these small communities simply because you have a stranger come into your door with a clipboard or a pad. Right. You don’t know if that’s ice. You don’t know if that’s the tax collector. You don’t know if that’s an aggressive landlord. Right. There’s so many different factors that stranger could be. No answer the door for the censors. Now, those who do the the annual census, not sensors, census. Yeah. Those guys have done a great job of trying to market and look very friendly. Yeah. But it’s still and even just society in general. Right. Think about how our response to a visitor is in today’s day and age versus the past. There’s a comedian who does a whole stand up about how when the bell used to ring, we would grab the brownies in the tray and invite them in. And nowadays we kind of lay low to the ground and hide and try to see who it is without people knowing that we’re in the house. Things have changed when it comes to visitors.

Q: If you could name one or two things that you really hope could be a message from CVM to the world, what might they be?

A: Ooh, that’s a big question. So let me rephrase that. What would I want the world to know about small rural unincorporated communities or specific to Stratford?

Q: Either is fine, because they’re both.

A: I would like them to be aware of just some of the very basic daily needs that are consistently overlooked in these types of communities. For example, clean water is not something that certain communities ever have to think about. Or their water, like not having access to it, that’s just a given. In Lemoore, when we want to cut back on water, we just change our sprinkler days from Monday, Wednesday, Friday. In Stratford, you drive your truck down to the local water district and get some bottled water until they turn the water back on or the well is filled, you know what I mean? I guess I’d like people to understand just how underserved these populations are with basic needs that other communities don’t have to worry about. Things like a safe turning lane into your community, things like consistent access to clean water, and things like proximity to basic commerce like fresh produce. You have people who go out daily and pick fresh produce that lines the shelves of our beautiful supermarkets. And in a town like Stratford, you cannot go anywhere and buy a fresh head of lettuce and some fresh tomatoes within your own community. Access to things like fresh produce. There are a lot of people from the bigger communities who don’t realize that these towns exist. We are being overlooked on basic human needs.

Q: What’s the next largest town?

A: Yeah, so our closest community is the one I live in now called Lemoore. Lemoore has one of the largest naval bases in the country. Actually, they filmed Top Gun, the new Top Gun, they filmed it at Lemoore Naval Base. So there’s some crazy stuff, right? The Lemoore Naval Base, we have a wave pool, right? This wave pool was built. It’s one of a kind in the world, right? It’s about four miles from Stratford. Now remember that our community ran out of water. Right. This wave pool takes gallons and gallons of water to just run so that guys can surf. Now, I don’t, you know, I actually, I enjoy that it’s there because it does bring commerce and activity to Lemoore. Sure. But just the contrast, right? And resources just down the street. And then we have Tachi, one of the most successful casinos in California. Tachi is down the street as well. These are all within two to three miles of Stratford. And they all have turning lanes off the 41 for easy access, right? We clearly have the ability to get large amounts of water to these areas. It’s just a matter of finances. We’re clearly able to build a roundabout into Stratford to slow down the traffic and get people safely in. It’s a matter of finances, resources. And so sometimes it kind of feels like the priority isn’t necessarily people, but what’s going to create the most revenue, unfortunately. That’s a reality anywhere in the world. Of course, that’s not exclusive to us.

Q: Well, Rob, we really appreciate talking with you and hearing your stories and the work that you’re doing.

A: Thank you.

Leave a comment